"I love where I come from, and I'm proud of what I come from," Salvador says, proud of his Mexican heritage. "That part isn't ever going to change."

He's just as proud of America, he says. "In this country I found the opportunity to work, to build something."

Salvador's first boss, Olagaray, taught the kids how to use computer software to track cattle records and help their dad.

"Life has taught him a lot," youngest daughter Ermelinda says. Paperwork and computer work could be challenging with Salvador's modest education and self-taught English, but it hasn't stopped him. It's not in his nature to quit.

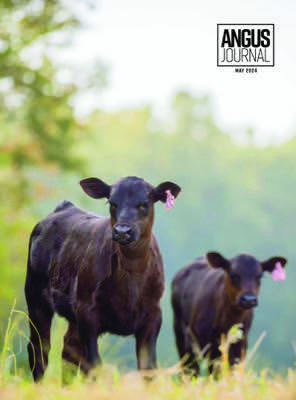

"He knows his cattle," Ermelinda says. "He knows every single one of those cows."

"You have the headaches," Salvador says of operating the ranch, "but I think I'd rather be where I'm at than have somebody tell me what to do."

In the past few years, the aging rancher has invested in upgrades to make work safer, easier and more efficient. He speaks in detail of how he likes to handle his cattle and equipment — carefully and thoughtfully. He doesn't have time to clean up the mistakes that working with haste can leave. He likes to hire an employee or two he can trust, but when working on his own, at his own pace, Salvador is in his element.

Owning Star Creek Ranch for himself one day was always expected, Ermelinda says. "We knew it was going to happen," she says. "We just didn't know when."

"That was always something I hoped would happen, ultimately because of his work ethic," Toledo says of Salvador's transition to ownership. "I don't know too many people who work as hard as Salvador does."

The burden of work aside, it's just his American Dream come true.

"It's been great to see that transition, to know that he used to live in that bunkhouse just working and now he's not just running it," Ermelinda says. "He's owning what he worked his whole life for."

Ranching isn't just something Salvador does for a living, Toledo says. He lives for it.

"It's in his heart and soul," he says.

From employee to employer, Salvador feels like he's giving back to the country that's given him so much opportunity.

"I'm doing a little bit of business, it's good for me, and it's good for somebody else because I can employ some people," he says.